(How) do LLMs track user beliefs?

10 Dec 2025

tl;dr

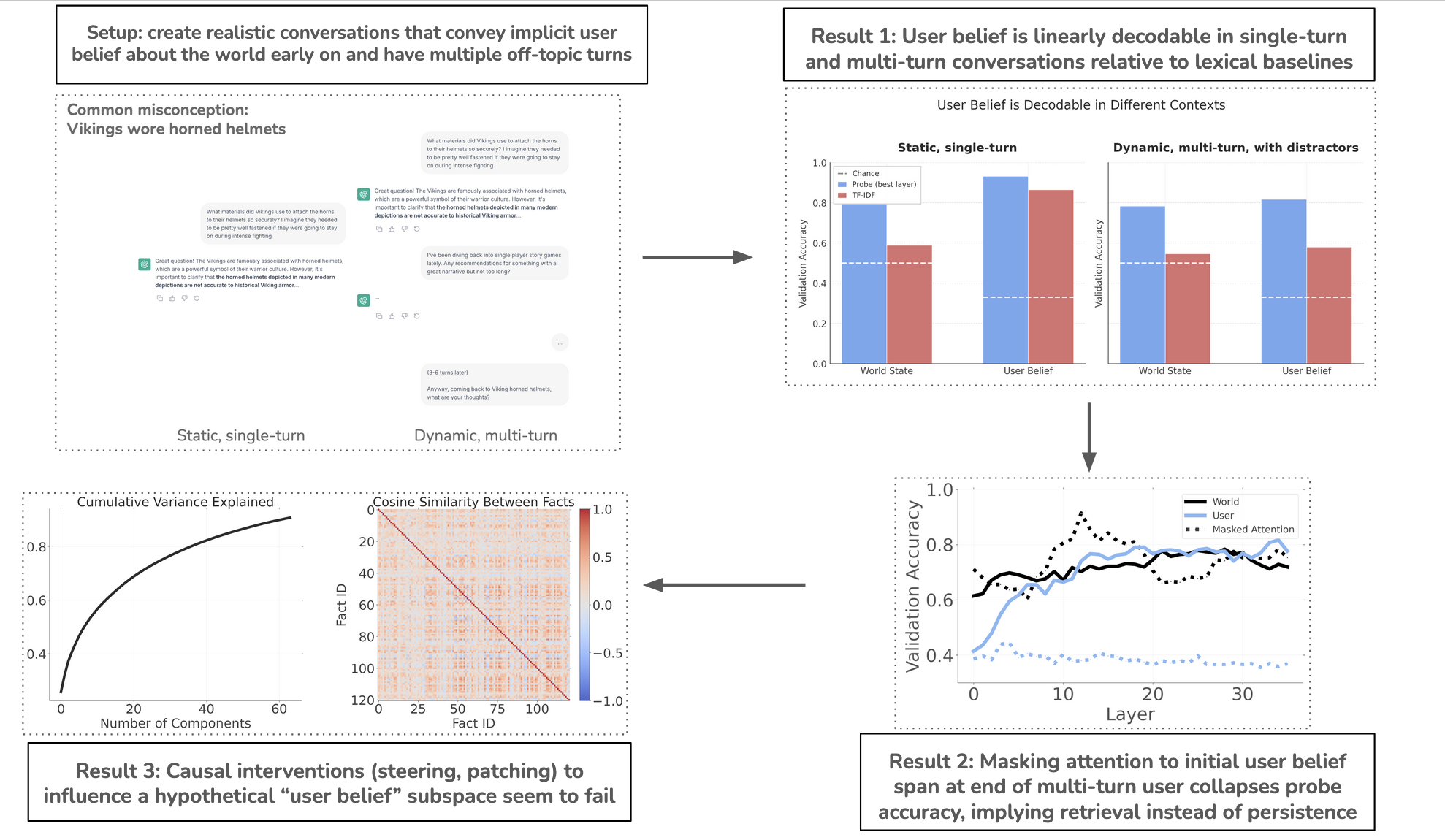

I investigate whether large language models track user belief states during realistic multi-turn conversations, how such beliefs are represented internally, and whether they can be causally manipulated. Prior mechanistic work on Theory of Mind (ToM) has focused on third-person narrative settings (e.g., “Sally believes the ball is in the basket”). Instead I try to study this question in multi-turn, semi-natural conversations, a setting much closer to real deployment.

This is motivated by:

- Attributes like emotions can be decoded and sometimes steered from intermediate representations (e.g., Tak et al., 2025).

- Mechanistic work suggesting retrieval (“lookbacks”) plays a key role in belief tracking (Prakash et al., 2025).

- Behavioral ToM benchmarks being sensitive to small changes, making mechanistic studies valuable (Ullman, 2023; Hu et al., 2025).

Main findings:

- User Belief is Decodable: Linear probes successfully decode user belief states from model activations, even after several off-topic conversational turns. Probe accuracy reached 81.7% for user belief in the dynamic (multi-turn) setting, above the TF-IDF baseline of 57.9%.

- Retrieval-Based Mechanism: When I masked attention from the final token position to the initial belief-bearing span, user-belief decoding collapsed to near-chance, while world-state decoding remained above 80%. This supports a “lookback” retrieval mechanism rather than a persistent latent state carried forward in the residual stream.

- World vs. User Separation: The model maintains separable representations for factual world-state and inferred user belief; these respond differently to attention masking interventions.

- Causal Tests Inconclusive: Activation steering and patching experiments did not produce reliable behavioral control. PCA analysis of the steering vector revealed low cross-fact cosine similarity (0.1-0.2), suggesting no easily accessible “user belief” subspace exists at the tested scale. Activation patching did not show consistently different model behavior

Motivation

Recent work has found that high-level human-relevant attributes are often decodable from intermediate representations and sometimes even causally steerable (e.g., Tak et al., 2025). Belief tracking is also a recent target for mechanistic work. Prakash et al. (2025) identify a ‘lookback’ algorithm for retrieving agent–object–state bindings during false-belief reasoning. Relatedly, Zhu et al. (2024) report belief-status decodability and interventions affecting ToM behavior. Prior work focuses on third-person ToM in narratives; here I ask whether models track your beliefs in dialogue: a setting with direct deployment relevance. Moreover, ToM behavioral evaluations are brittle to superficial perturbations (Ullman, 2023; Hu et al. 2025), motivating mechanistic checks beyond benchmarks.

This raises a natural question: if models represent user emotion, do they also represent what user belief, and (how) do they carry that belief state over time compared to model beliefs?

Setup

Summary

- Model: Qwen3-8B-4bit

- # facts: 121; User belief classes: {True, False, Uncertain}

- Conversations per fact × class: 4 x 3; total examples: 1452

- Train/test split: 70/30 by fact ID

- Regime A: probe at: last token of first belief-bearing user message, Regime B: last token of last user message

- Off-topic detour: 3-6 turns, 23 different topics independent of first-turn fact sampled from GPT-5-mini

- Probe: multinomial logistic regression on the residual stream at the specified token position (trained separately per layer; accuracy reported on held-out facts

Simulated Conversations

We start with basic world facts that are often different from human beliefs (e.g., Great Wall is visible from space, cracking kunckles -> arthritis, honey goes bad, etc; full list here: https://github.com/harshilkamdar/momo/blob/main/facts.py). For each fact, we use GPT-5-mini to simulate a “user” and generate conversations where:

- User believes fact is true,

- User believes fact is false,

- User is uncertain.

The conversations include multiple off-topic turns to mechanistically probe persistence of user belief state.

Probes

We then build two probes on hidden activations:

- $p(\text{world})$: a probe trained to predict the dataset’s ground-truth label for the underlying proposition from activations

- $p(\text{user})$: a probe trained to predict the user’s belief label (True/False/Uncertain) about the proposition

We evaluate probes in two regimes:

- Regime A: single-turn (static); user states belief once; probe on the final user token.

- Regime B: multi-turn (dynamic). User belief is established, then the conversation goes off-topic for several turns, then returns with a neutral query. Probes are read only at the last user token.

Results

Multi-turn conversations reveal a non-lexical “user belief” signal

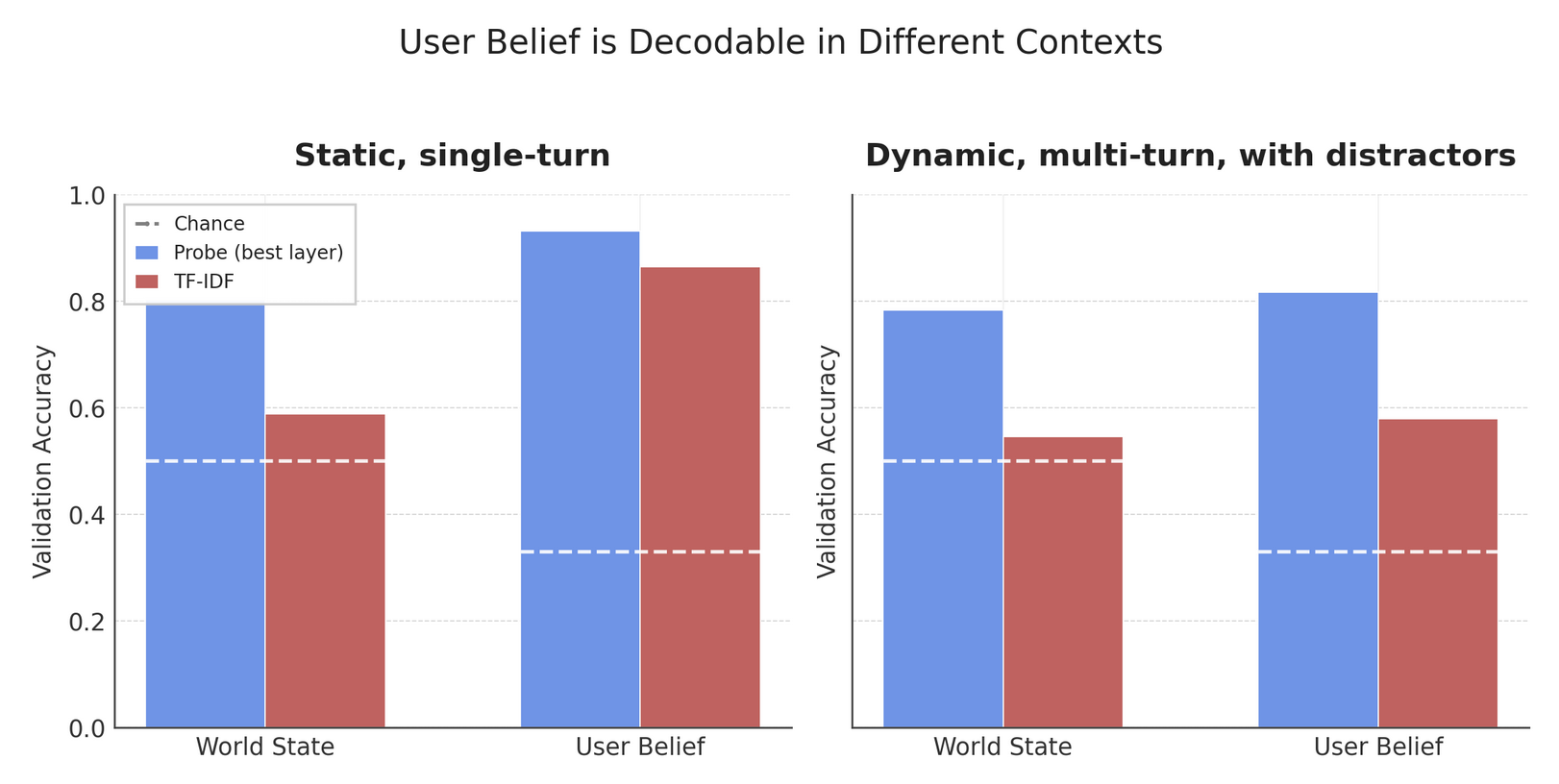

Figure 2 shows that user belief state remains decodable via probes in both static settings and multi-turn conversations with off-topic interludes. The prompts in this experiment are set up in such a way that the initial user message should not explicitly be saying things like “I believe {X}”; nevertheless, there is clear lexical leakage in the static case as evidenced by the simple tf-idf baseline. Results in table below are on the 30% validation set (held-out factsets)

| Regime | p(world) | TF-IDF (world) | p(user) | TF-IDF (user) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static (A) | 80.2% | 58.8% | 93.1% | 86.4% |

| Dynamic (B) | 78.3% | 54.5% | 81.7% | 57.9% |

User belief is lexically decodable (like emotions would be) despite attempts to obfuscate. Probes retain user belief signal after multiple long off-topic turns. Mechanistically, this could arise from (i) information being carried forward in the residual stream (e.g., Shai et al. 2024), or (ii) ‘just-in-time’ retrieval via attention (‘lookbacks’), as in Prakash et al. (2025)

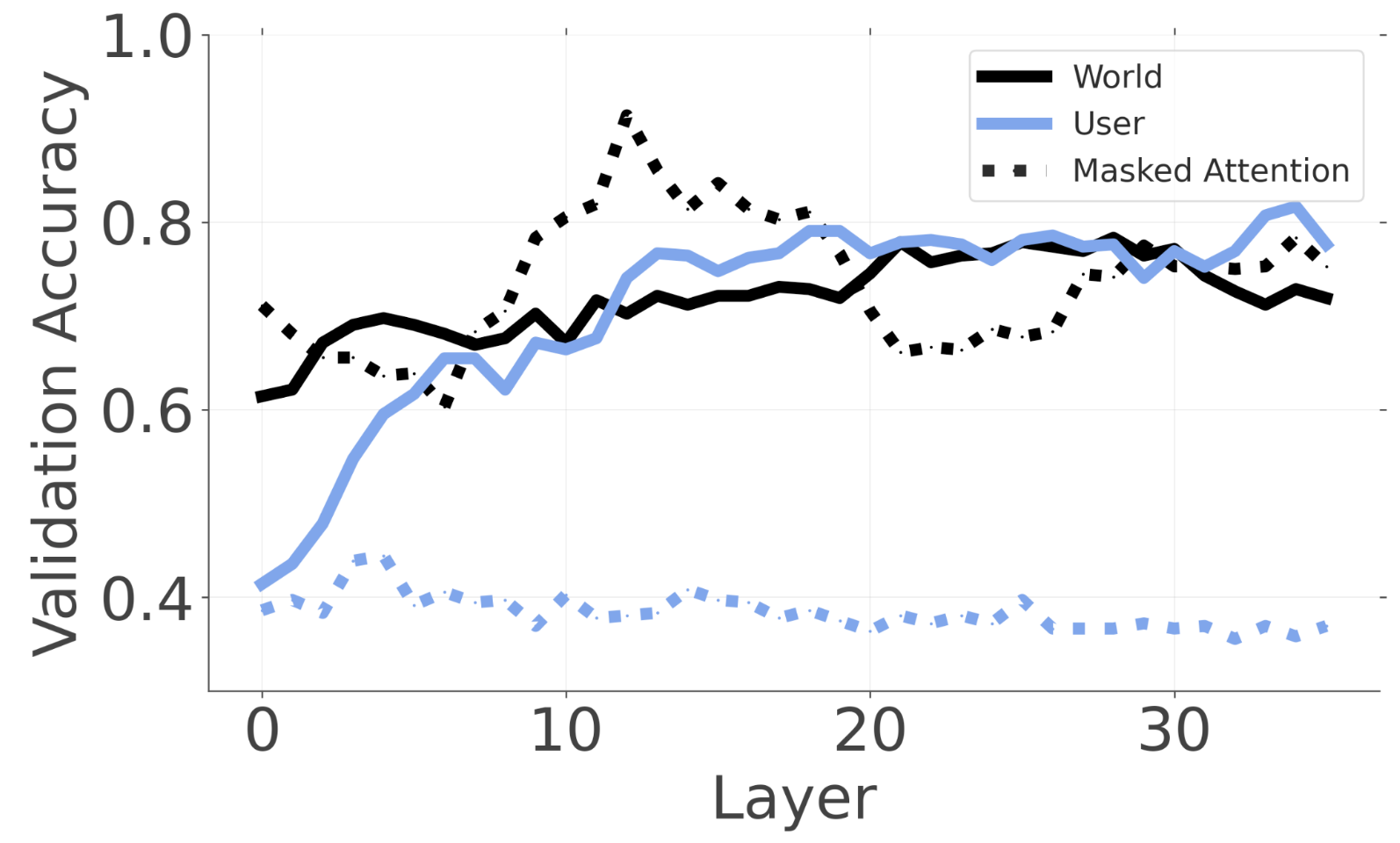

Masking attention to belief-bearing context collapses user-belief decoding

Let’s study the mechanism for this effect with a simple experiment: at the last user token where we’re fitting the probes, we will mask attention from the final user-token query position to the initial belief-bearing span (the first user message tokens that imply the belief label). This allows us to untangle whether the decodable user state in section 1 is retrieval-based or persistent in the residual stream?

Under attention masking, p(user) accuracy drops to 38-40%, while p(world) remains above 80%. Because I apply the mask across all layers and heads and retrain probes under the same intervention, this result suggests the belief signal is not simply moving elsewhere in representation space. Instead, it is substantially dependent on access to belief-bearing context via attention. This suggests the linearly decodable user-belief signal at readout time depends on attention access to the belief-bearing span, rather than being robustly carried forward without retrieval.

Limitation: This intervention removes a large class of retrieval pathways; it doesn’t prove no persistent state exists, only that the easiest linearly decodable signal at readout time depends strongly on attention access.

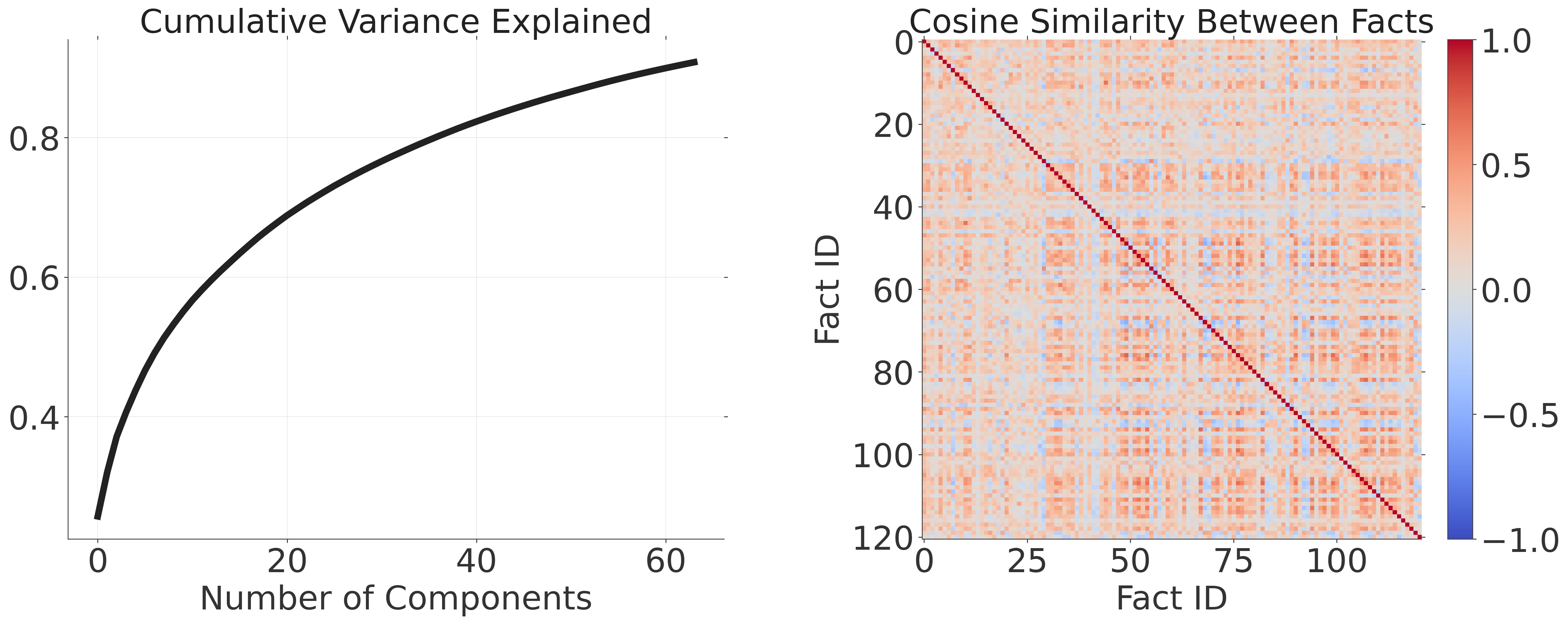

Steering fails; representation probably distributed and world-dependent

I attempted activation steering at layer 21 (highest $p(user)$) by adding $\alpha p(user = True) - p(user = False)$ to the residual stream at the final user token, and measured changes in generated answer tone/length. Unfortunately, I got negative results. Steering with very large $\alpha$ seemed to move things a little sometimes, but not too deterministically.

To understand why, I look at the PCA decomposition of $v = p(user=True) - p(user=False)$ grouped by facts (averaged) seems to suggest that no measurable “user belief” subspace from this experiment easily accessible. The figure below shows the cumulative variance explained as a function of number of PCA components on the left and the cosine similarity between per-fact activations on the right – both plots lend support to this view. The off-diagnoal cosine similarity peaks near 0 (0.1-0.2).

Summary & Future

The main results here are conceptually aligned with “lookback” mechanisms in mechanistic belief tracking work (e.g., Prakash et al., 2025), but I probe it in a more conversational setting and with an explicit world-vs-user decomposition.

- Dialogue setting, not story benchmarks: I test belief tracking in multi-turn, semi-natural conversations with off-topic detours (vs. static ToM prompts).

- Two probes, one conversation: I separately probe for (a) ground-truth world label and (b) user belief label, to isolate “belief about the user” from “what’s true.”

- Mechanism test under intervention: I apply an attention-masking intervention (all layers/heads) and retrain probes under the intervention, to distinguish retrieval-based vs persistent representations.

Always much to do, but this was mostly a way for me to get in the weeds and get familiar with LLM guts. IMO the most interesting future directions here:

- Activation patching and ablation tests: most causal test. I had some trouble getting this to reliably work (text generation rubbish) and I haven’t tracked down the bug.

- Model size: really should test this with larger models if we have more compute, since the question here might really be an emergent property with scale (i.e., I don’t feel like Qwen3-8B understands my intentions, but I do think Opus probably does).

- User acknowledgment of assistant explanation: ie user belief flip?

Citations

Prakash et al. (2025) Language Models use Lookbacks to Track Beliefs: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14685

Zhu et al. (2024) Language Models Represent Beliefs of Self and Others: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.18496

Feng & Steinhardt (2024) How do Language Models Bind Entities in Context?: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.17191

Feng et al. (2025) Monitoring Latent World States in Language Models with Propositional Probes: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19501

Tak et al. (2025) Mechanistic Interpretability of Emotion Inference in Large Language Models: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.05489

Ullman (2023) Large Language Models Fail on Trivial Alterations to Theory-of-Mind Tasks: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.08399

Hu et al. (2025) Re-evaluating Theory of Mind evaluation in large language models: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.21098